Homebodies

by J.D.H.

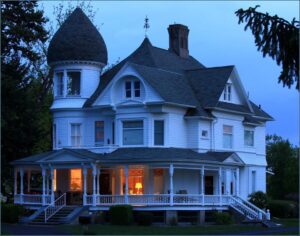

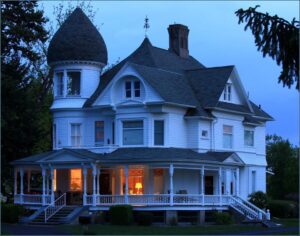

Dr. Loris Limm, eminent surgeon and pillar of the community, stepped into the foyer of his house. It felt good to be home. It was drizzling outside, and the good doctor tossed his wet coat onto the back of a chair in the hallway, thoughtfully removed his shoes, and placed his laptop computer on a small, antique table. To his right, the door to the library was slightly ajar. Light from the room was filtering out into the foyer.

Dr. Limm began to open the library door, but then hesitated. A frown creased his handsome, middle-aged face.

From within the room, he could hear the smack-flutter of damp flesh on paper, and this distressed him. It reminded him of his wife, Eleanor, who had the annoying habit of licking her index finger before turning every page of whatever book she happened to be reading. A harmless enough thing, certainly, but to Dr. Limm that “wet” sound was infinitely more grating than the proverbial fingernails on a chalkboard.

And now it would seem that one of the twins — perhaps both — had picked up Eleanor’s irritating tic. But then he chastised himself, recalling that his children would never be guilty of such obnoxious behavior.

**

Dr. Limm pushed the door open and, sure enough, his children — the boy Neil and the girl Lisle (affectionately nicknamed “Pincushion” by the family) — both had their noses in books. Of Neil, Dr. Limm could see but the top of the boy’s curly brown hair, just visible above the backside of a roan-colored sofa. Neil’s book was propped against a throw pillow. Lisle he could see in her entirety as the girl lay sprawled on a shaggy rug near the fireplace. Her book was splayed upon the rug.

“Father!” Lisle cried. No such greeting came from his son, but Dr. Limm could hear a faint rustle of shifting plastic in the vicinity of the boy.

“Children,” Dr. Limm graced them with a barely perceptible smile. He did, however, lean over the sofa to ruffle his son’s unruly crown of hair. “Studies, or pleasure?”

“Studies, father,” replied the boy. “Father, what will we eat tonight?”

Dr. Limm ignored this and turned to his golden-haired daughter. “And Lisle, studies or pleasure?”

“Pleasure, father. Mother says I am ahead of Neil in my studies, and so I am waiting for him to catch up.”

“And what are you reading for pleasure?”

“A Farewell to—“

“Father,” her brother cut in: “Might we have hamburger and potato salad for dinner? It’s Thursday, and—“

“Let me check with your mother,” said Dr. Limm. “Now get back to your books. I don’t want to interrupt Neil’s education, and Hemingway waits for no man.”

“Nor girl!” squealed Lisle.

Dr. Limm graced them with a second weak smile, and pulled the door shut as he moved back into the hallway.

**

A light at the end of the passage informed him that his wife of 33 years was in the kitchen. The light was blue-tinged, which indicated, not surprisingly to the doctor, the glow of a television. No studies or Hemingway for Eleanor. As Dr. Limm entered the smallish kitchen, he beheld the usual scene: Eleanor on her loveseat, feet planted on an ottoman, hand deep in a box of some-kind-of-snack, and the television tuned to some “reality TV” absurdity.

On the screen, a half-dozen Southern teens were filling the bed of a pickup truck with water from a garden hose. They had lined the truck’s bed with a large plastic sheet, and were attempting to create a Kentucky poor kids’ version of a backyard swimming pool.

“Neil is asking about a special meal again,” the doctor said, after glancing at his wife to ascertain whether she was awake or asleep. “I told him I would check with his mother.”

One of the redneck girls on TV, the doctor noted, had managed to lose her bikini top. MTV had tactfully pixilated this moral offense. Eleanor either heard nothing her husband had said, or determined that no reply was required. Her nose twitched, as though something foul-smelling had suddenly entered the room, but her eyes stayed glued to the TV.

Dr. Limm followed her gaze to the flat-screen television. Every other word out of the teenagers’ mouths was being “bleeped” by the network’s censors. Dr. Limm sighed.

**

“The children on this show are animals,” Eleanor whispered, more to herself than to her husband. “It’s obvious we made the right decision.”

Dr. Limm took a seat in a rocker and sat in silence for some minutes, observing with his wife the hedonistic behavior of the MTV kids. “They are having a wonderful time of it,” he said at last. “Give them five years, and they’ll have a wonderful time of it behind the walls of some penitentiary, or in the waiting room of some seedy abortion clinic.”

“We made,” repeated Eleanor, “the right decision. Oh, yes.”

Dr. Limm nodded his head in assent. “Discipline may be short-term pain, but it’s … it is long-term gain, I assure you.”

“You don’t have to tell me, Loris.”

“I’m sure I don’t. Those children on your television program, assuming they have parents, will wind up costing them a bundle. Parents must do what they must to maintain discipline. And to keep children safe from the wicked influences of the outer world. At least, whenever possible.

“And if that means their children must suffer some inconvenience, well.” The doctor paused to consider. “I’m not suggesting that I don’t enjoy a … respectable income, but even Neil and Lisle, at times, cost me an arm and a leg.”

Eleanor burst out of her loveseat as though the fumes she detected earlier had blossomed into a full-blown nuclear explosion. In two steps she was standing above her husband, delivering one vicious slap to his left cheek, and a follow-up blow to his right.

Dr. Loris Limm’s eyes widened in shock, but he regained his composure almost immediately. He looked down at his lap in shame. “I’m so sorry, Eleanor. I … I didn’t think. That was careless of me.”

**

The rustle of plastic against wood caused them both to look back at the kitchen entrance.

“Father,” said Neil from the doorway. “There was a joke in a book and it’s upset Lisle terribly. The joke was: Three boys come to the door of Little Johnny’s house. Johnny’s mother answers the door and one boy says, ‘Mrs. Smith, Mrs. Smith, can Little Johnny come out to play baseball?’ And the mother tells them, ‘Now boys, you know that Little Johnny has no arms nor legs.’ And the boy says, ‘That’s OK, Mrs. Smith, we just need him to be second base.’’’

Neil paused and looked from one parent to the other. “Lisle is awfully upset.”

Dr. Limm looked down at the stump of his 32-year-old son, whose arms were amputated below the elbows and whose legs were missing below the knees. The doctor frowned when he noticed the plastic bag the boy had dragged down the hall with him. Behind the boy, Lisle, also 32 years old and similarly dislimbed, shed tears from the spot on the hallway carpet to which she had slithered.

“Neil,” Dr. Limm admonished, “Your colostomy bag is leaking. Please clean up after yourself at once.”

“Neil,” added Mrs. Limm, “Guess what? Hamburger and potato salad — tonight!”

THE END

Click here for the index of short stories.

Click here to see all of the stories.

© 2010-2024 grouchyeditor.com (text only)